Imagine if you could take a time machine and visit an ancient Hohokam agricultural field 1,000 years ago. The crops in that field would contain corn, green-striped cushaw squash, and tepary beans – varieties familiar to contemporary Pima and Tohono O’odham farmers. But you might also find an unusual, yet majestic, bean known today as jack beans (Canavalia ensiformis).

By Melissa Kruse-Peeples, NS/S Conservation Program Manager. Published on March, 20, 2015. Updated April 17, 2018.

Imagine if you could take a time machine and visit an ancient Hohokam agricultural field 1,000 years ago. The crops in that field would contain corn, green-striped cushaw squash, and tepary beans – varieties familiar to contemporary Pima and Tohono O’odham farmers. But you might also find an unusual, yet majestic, bean known today as jack beans (Canavalia ensiformis).

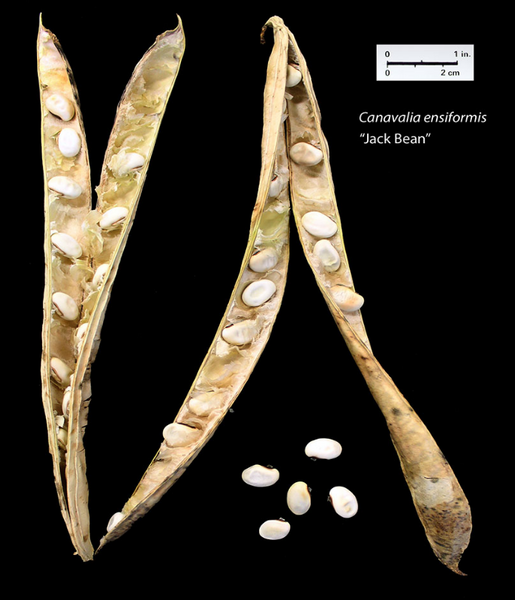

Jack beans have been recovered from numerous archaeological sites throughout Central and Southern Arizona, including the Hodges Ruin located just a few miles from the Native Seeds/SEARCH Seed Bank in Tucson. Jack beans, an introduction from tropical environments of the Central and South America, appear as part of the Southwestern agricultural history around A.D. 700. However, this bean has just about disappeared from agriculture in Arizona. It was last documented among Pima fields in Sacaton, Arizona in 1938.

Native Seeds/SEARCH conserves 2 accessions of Canavalia ensiformis. One collected from a mestizo dooryard garden outside of Navajoa, Sonora and another from Wilcox, Arizona that likely derived from a commercial source rather than a historical lineage of the area. In 2014 we were able to successfully regenerate one of these aging accessions to provide fresh seed samples. Through future growout efforts we hope to increase the seed supply and once again see these beans growing along the banks of the Santa Cruz and Salt Rivers. In 2017 I successfully grew a crop of Jack Beans in my backyard garden in Phoenix, Arizona. Seeds from this harvest are currently available online and in store.

Jack beans, also called wonder beans, generally require more water than desert-adapted tepary beans. However, once established the incredibly deep tap-root allows them to be drought resistant. This is an important characteristic because they require a long growing season of 150 days or more to set seeds. As with other types of beans, Canavalia are frost sensitive but have been documented to grow as semi-perennial bushes. I can attest to this. My seeds planted in March 2017 produced flowers in the late summer and dried pods were fully harvested in December and January. Plants did die back during the mild Phoenix winter but once temperatures rose in Feb/March the vines leafed out and immediately began to flower. At this time, April 2018, my 1 year old plants are setting another round of pods. Vines do not have tendrils to grab but they can easily be twisted to grow up on a trellis. Vines reach about 6-8 feet in length.

The flowers of this species are gorgeous and resemble their distant cousins in the Phaseolus genus. The plants produce large vines and easily produce upwards of 50 pods per plant.

The enormous pods reach over a foot in length and can be eaten like a green bean when young, only a few inches long. Dried beans are mildly toxic and should not be eaten raw or in large quantities. They should be rinsed thoroughly. Unfortunately our 2014 harvest was modest and we sacrificed culinary experimentation in order to have more seed available to increase. The 2017 harvest was abundant but we decided to make seeds available to other growers rather than cooking up a pot of beans.

The revival of Jack Beans within Arizona fields is an important example of the power of agricultural biodiversity conservation. Local, regional and global food security depends on this diversity, particularly as we adapt to increased temperatures and prolonged droughts. The Native Seeds/SEARCH seed bank's primary function is to conserve this genetic diversity for the future and to revive traditional crops within fields and tables today.

A version of this article first appeared in The Seedhead News Number 119, Winter 2015.